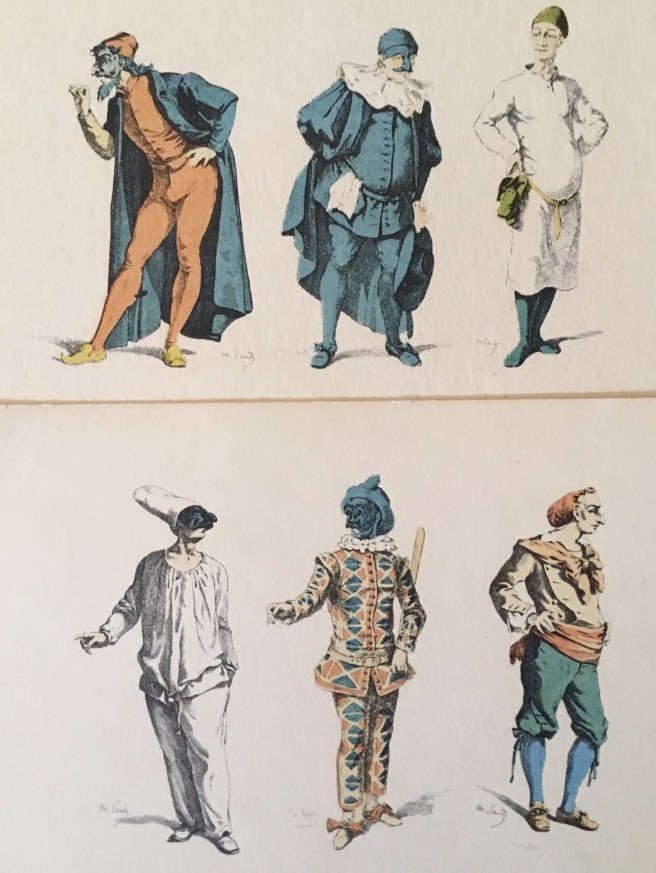

We think of a mask as a covering for a performer’s face – fashioned of leather, wood, paint, fabric or some other material – and expressive of a character. (The mask may cover the face, but as Carlo always said, “The mask doesn’t conceal, it reveals!”) In Commedia, the characters were referred to as masks. This acknowledged that the entire performer was a mask, from head to toe. The physicality of the whole body was synonymous with the mask.

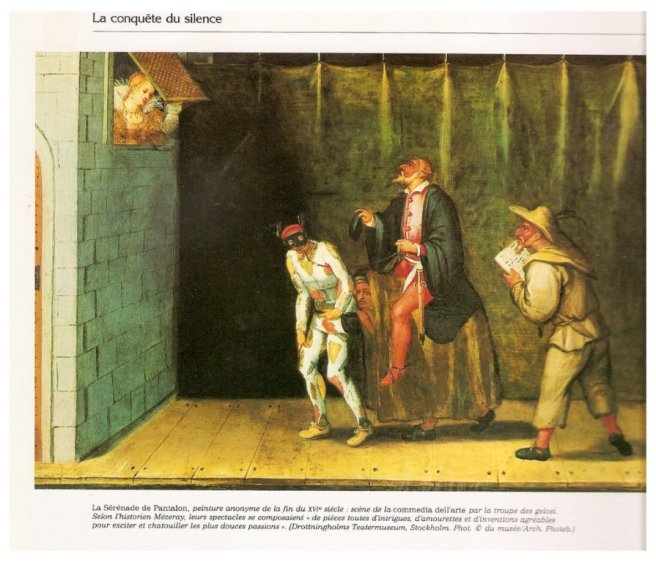

Pantalone’s face features heavy eyebrows over a hooked nose – but you cannot play the character without the tilt of his pelvis, the bent knees and the shuffling gait. The mask on Dottore’s face is little more than a forehead and an impressive nose – but the rest of his mask is his prominent belly, his narrow base (feet too close together to support his girth), and the index finger he waggles to make a point. Arlecchino’s face features a child’s button nose, and the actor supplies the large tongue and the wide-mouthed expressions of wonder. And the feet! Arlecchino’s feet – prancing, skipping or planted – are very much part of his mask.

One of the greatest challenges in teaching physical theatre is to get the performer to support the mask. The mask over the face is only the most distilled part of a spirit that informs every element of the actor’s physicality, movement and rhythm. While we may bemoan the ways in which film has concentrated our attention on the actor’s face in close-up, this total physicality is something that good performers have always instinctively understood. The great English actress Wendy Hiller used to say that she needed to get a character’s shoes right. Once she had the right feet, she could inhabit the character properly.

Physical theatre is alive and well in actors like Daniel Day-Lewis, Meryl Streep, Joaquin Phoenix, Tracey Ullman and Johnny Depp – who instinctively understand the power of supporting the mask even on film.