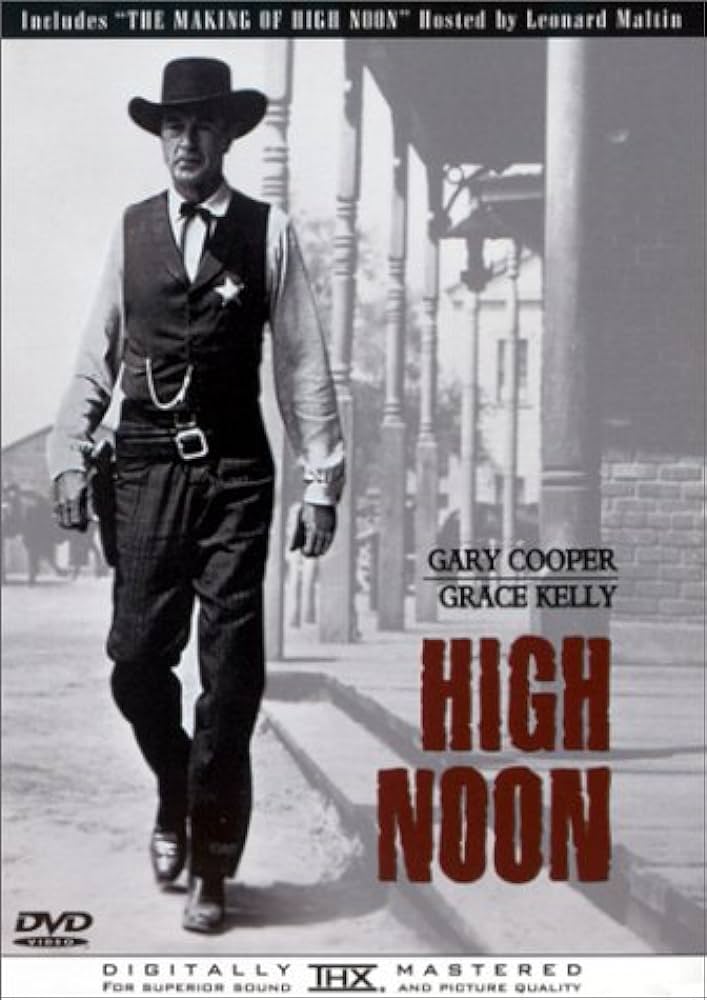

… that is the question. For many years, the Hollywood star system depended on actors who were recognizable in every movie. What is the difference between Jimmy Stewart and Marlon Brando? Both were excellent actors, but they approached their roles in different ways during their long careers. Stewart was cast in roles that made use of his own personality. Was he simply playing himself all the time? No, but he was matched up with scripts that suited him, and directors who guided him to bring his own qualities to the role. The same could be said for Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Fred MacMurray, Gregory Peck, Alan Ladd, Richard Widmark, Gary Cooper, Edward G. Robinson and Sidney Poitier.

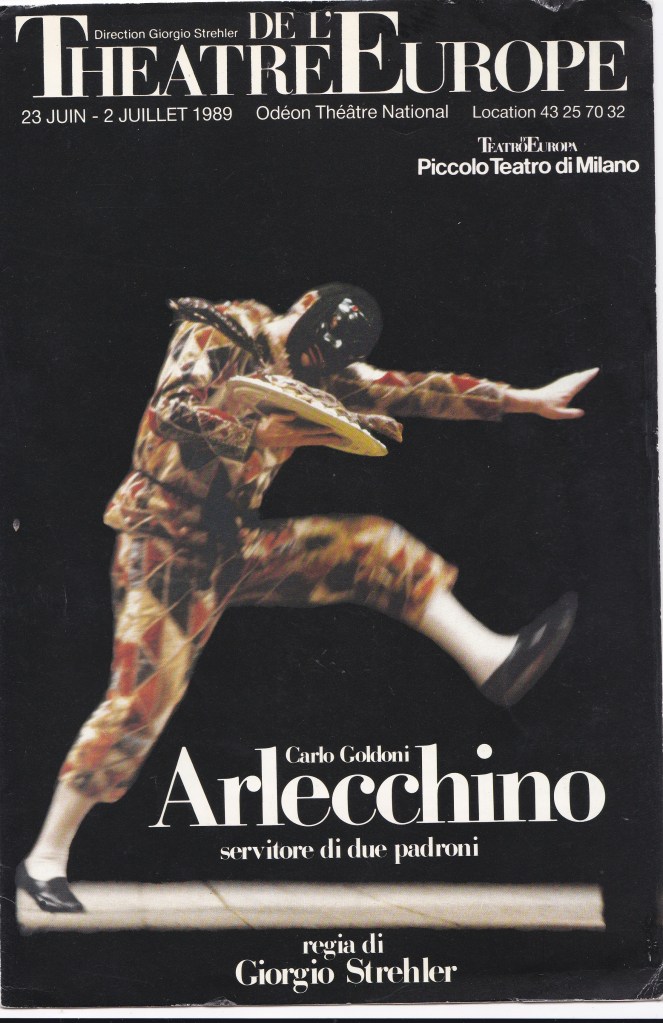

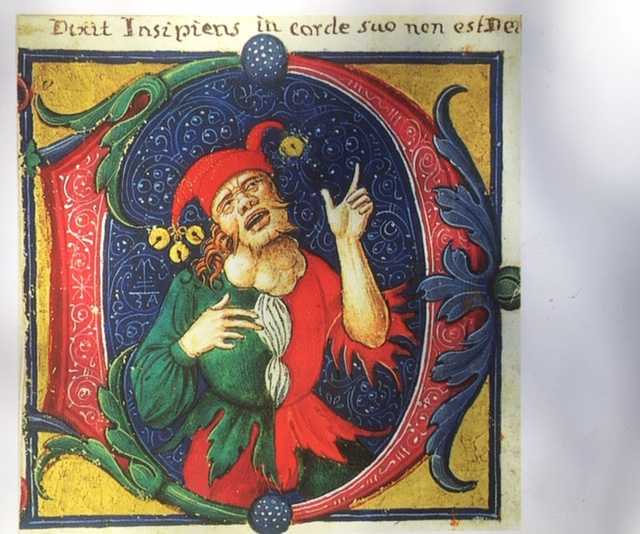

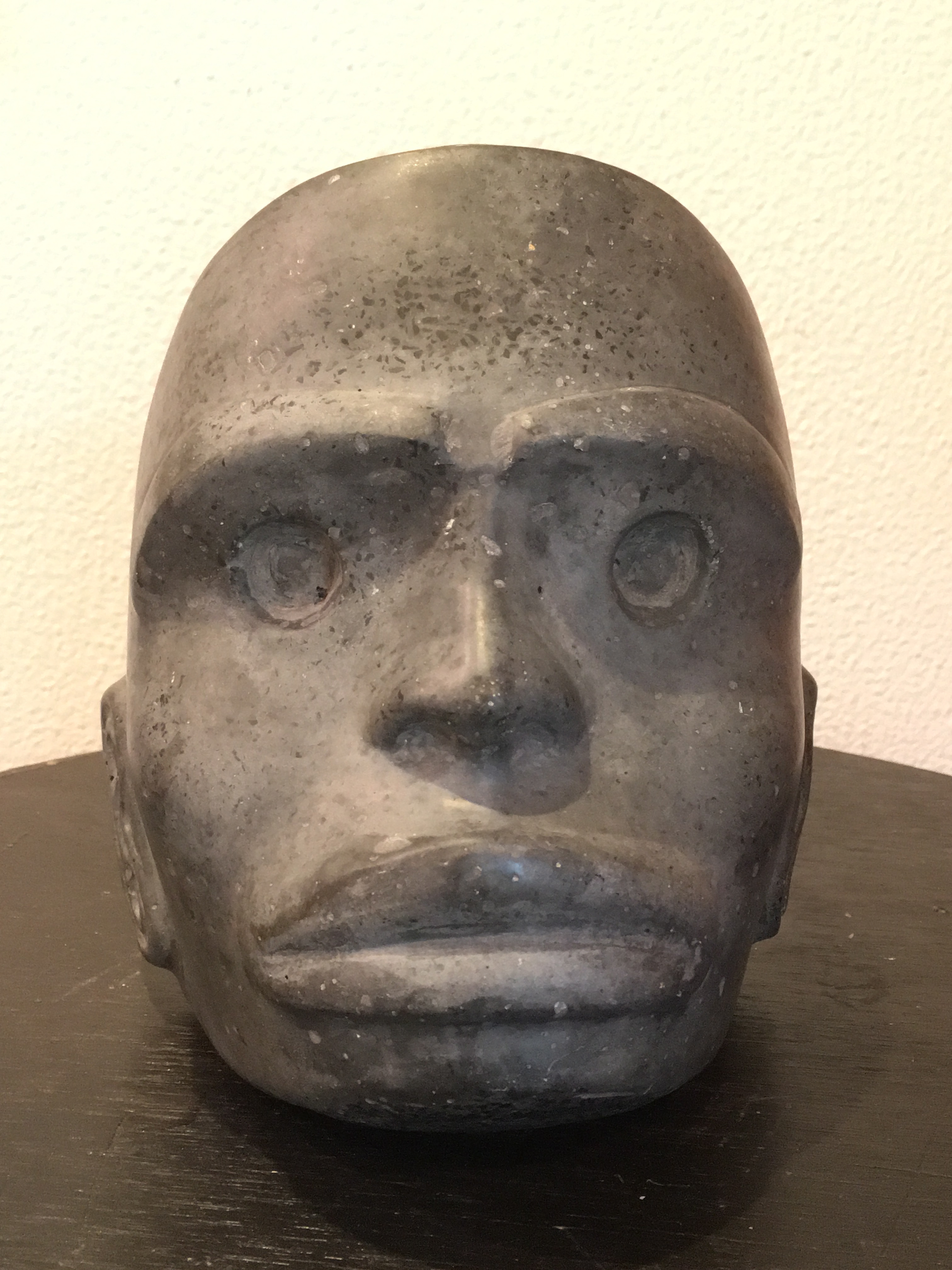

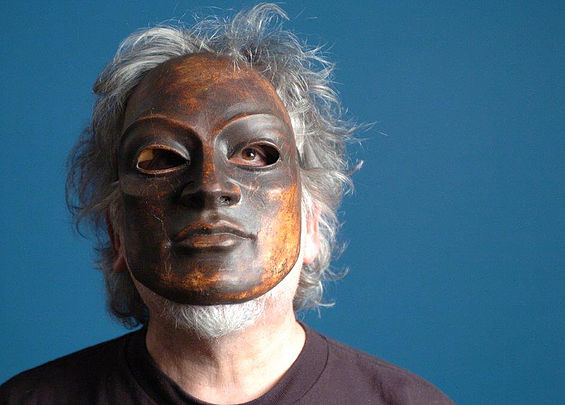

The training I received (and offer) is more oriented to helping an actor change their voice, posture, rhythm and over-all physicality, and their face through makeup. Rather like wearing a mask in a Commedia dell’Arte play. Hence my formula for Change = M+O+R+E. (Movement, Objectives, Relationships and Energy). Think of the difference between Brando as Stanley Kowalski and as Sakini in Teahouse of the August Moon. Or Gary Oldman as Sirius Black in the Harry Potter films, as opposed to Winston Churchill in The Darkest Hour. In this category of actor you will find, in earlier times, Charles Laughton (think of his Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Lon Chaney Sr., Boris Karloff, Jose Ferrer. And, more recently, Joaquin Phoenix, Javier Bardem, John Turturro and Jeff Bridges.

This does not mean that Gary Cooper is anything but a brilliant actor in High Noon, nor Cary Grant in Notorious. Simply a different style of acting. Women in Hollywood were not given much range for a long time. But now we have Meryl Streep, Helen Mirren, Frances McDormand and many others who are able to change from role to role.